Brigadier General

U.S. Army Air Corps

circa November 1944

The words, “Christmas Eve”– for us in the Northern Hemisphere– conjure visions of shivering carolers, cups of steaming cocoa, and trees graced with twinkling lights. But 74 years ago Christmas Eve, the bomber crews and aircraft-maintenance crews of the U.K.-based U.S. Eighth Air Force (8AF) had different things on their minds: target charts, bomb loads, and Nazi fighters.

For days, the “Mighty Eighth”, because of bad weather, had been unable to help resist a Nazi counter-offensive we know as “The Battle of the Bulge”. If unchecked by Allied airpower, the Nazi thrust threatened to roll back the Allied advance toward the Nazi “Fatherland”.

However, the weather began to clear in the early hours of 24 December 1944. So, swiftly through the command posts, barracks, and hangars of 8AF, flew the words, “maximum-effort”: Every bomber that could fly was to be readied for a grand assault aimed at crippling the Nazi thrust.

This air-armada was to include more than 2,000 bombers and would be led by a 36-year-old U.S. brigadier general, Frederick Walker Castle. Castle had pinned his stars just a month before.

While Castle may have been new to the general-officer ranks, he was no stranger to the U.S. Army or combat. He had been born into a U.S. Army family in the Philippines in 1908. He went on to graduate from the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, in 1930. After graduation, Castle flew fighters for several years before returning to civilian life in 1934. There, he retained his military status by servings as an observation pilot with the New York National Guard.

After the United States entered World War II, Castle returned to active duty in early 1942. He served as a staff officer in the fledgling 8AF. He earned a reputation as a master of logistics by designing– literally from nothing– a system of bases, depots and supply routes.

“Castle’s enormous capacity for work appalled his colleagues”, a friend, Lieutenant Colonel (Lt. Col.) Beirne Lay Jr., wrote in the Washington Post in 1945. “He flogged himself beyond the point of normal endurance”.

Castle’s efforts were noted, for he bridged the gap between captain and full-colonel in just one year.

In June 1943, when Castle took command of 8AF’s 94th Bomber Group (94BG), he began earning another reputation: skilled, courageous combat leader. His new subordinates were amazed at his adherence to strict military standards of appearance, bearing and courtesy in the midst of a combat operation. Such standards, thought many 94BG combat veterans, belonged at a higher-headquarters such as that from which Castle had arrived. However, amazement became respect as Castle demonstrated an ability to calmly and successfully lead the group in the worst combat.

“The crews said, ‘Whenever Colonel Castle led a mission, we knew it would be a rough one. But we also knew that he would take care of us’”, Lt. Col. Lay wrote. And according to Lingering Contrails of the “Big Square-A” – A History of the 94th Bomb Group by Colonel Harry E. Slater, USAF (Retired), Castle’s motto was, “The only excuse for a bomb group is to put bombs on the target: results count”.

But Castle also demonstrated a soft-spoken manner and empathy for all for whom he bore responsibility. Gerald G. McClure of San Francisco, a former 94BG aerial gunner, recalled Castle, his rank obscured by flight coveralls, arriving at McClure’s B-17 for a mission briefing in June 1943. “We had other observers fly with us, and he was just one of many”, McClure added. “As we walked to the plane, he asked me what I thought of the mission. I assured him there was nothing to worry about because we would be back. I treated him like anyone else that flew with us.

“But, on the next mission”, McClure continued, “when he stepped out of the waist of the aircraft, his collar flipped up out of his flight coveralls and his eagle was in view. I apologized for addressing him as I had…and he said, ‘Think nothing of it, sergeant’”.

Castle’s leadership ability was recognized when he was promoted in April 1944 to command 8AF’s Fourth Combat Bombardment Wing.

That year, in November, he earned the rank of brigadier general. Just the following month came the Battle of the Bulge and 8AF’s maximum-effort of Christmas Eve. Castle was famous for leading the tough missions, but he was out inspecting bases in his command when the weather began to clear. This was one mission he almost missed.

For us the story of that night unfolds in the words of Castle’s chief-of-staff, Colonel Nicholas Perkins, as quoted in Lingering Contrails:

“I was his Chief of Staff and was in the Wing Ops on this night when the division weather officer informed us that the fog might lift at last. Lt. Col. MacDonald was to lead the wing…then we were assigned to lead the Third Division…then we got the word that the Third Division was the lead the entire Eighth Air Force on the biggest mission in history.

“Shortly, General Castle walked in looking very tired and said his driver had just let him out at ops and he only wanted to say he was home and on his way to bed. He asked if we were stood-down again, and I said, “No, we might be able to get off”.

He said, “Fine. It’s about time because we have to stop that breakthrough. I’ll see them off in the morning, but right now I’m going to bed”.

Perkins knew if Castle discovered the Fourth Wing was leading 8AF that day, he would bump Lt. Col. MacDonald and lead the mission. So, Perkins had told the command post staff to volunteer no information if Castle entered the room. Perkins recalled a feeling of relief as Castle left with no more questions.

For us, Perkins continues the story: “But he didn’t walk far, because in less than a minute, he stuck his head in the door and asked who was leading the Division. I had the say the Fourth Wing. He then came all the way in and asked who was leading the Eighth Air Force and I had to say the Third Division. “He thought a minute and said, ‘I’m sorry, Mac. I’m going to have to take your place. This is the kind of thing they pay me for, and this is the type mission I am expected to lead”.

And so Christmas Eve 1944 found one of the U.S. Army Air Corps’ youngest generals at dangerous duty not required.

As his lead ship, a Boeing B-17G Flying Fortress of the 487th Bombardment Group flew over “friendly” areas of Belgium, an engine began streaming oil. The problem became critical, so Castle elected to abort his aircraft’s continued participation in the mission.

As Castle’s aircraft banked down and away from the formation, a lone Messerschmidt Bf-109 attacked, quickly followed by three more Bf-109’s. With two engines ablaze, the aircraft commander gave the order to bail out.

De-briefing of survivors later established Castle had taken control of the aircraft. Further investigation determined that he held the aircraft level, inviting continued fighter attack, but also giving parachuting crew members a better chance of escaping the stricken craft.

What’s more, Castle did not jettison the bomber’s deadly payload, apparently to lessen the hazard to Allied ground forces. Oxygen bottles exploded, throwing flame through the fuselage. The, a wing fuel-tank exploded. The wing separated, and, so, the flaming aircraft spun violently to earth. Centrifugal forces pinned Castle and the aircraft commander within this flaming coffin.

Of the nine crewmen who had parachuted from the doomed aircraft, seven survived. Investigators credited their survival to Castle’s decision to hold the aircraft steady while they bailed out.

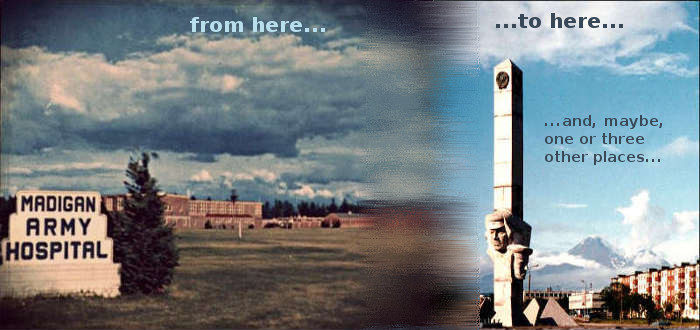

Because Castle sacrificed himself for others, he received the Medal of Honor posthumously in 1946. Also, Merced Army Air Field in California was re-named in Castle’s honor.

With the article published in the Washington Post, Lt. Col. Lay concludes the narrative:

“No man can say how far it is to the top of the sky. But those who have fought the enemy in the blue upper levels where the vapor trails form, and where the mist between life and death is thin, believe that men like Castle fly on at the high altitude from which none return to earth”.

Originally published in The Valley Bomber, Castle AFB, December 1983

© 2019, 1983 Landis McGauhey, First Lieutenant (R), USAF, medically-retired